Windowed Worlds

Tuesday, August 7, 2018

Sunday, July 20, 2014

Does your story have good tread? (Or, "how to fill a blank page".)

You also have a blank page.

You put down a few words of that first draft, ignoring the snoring sounds from your internal editor. You stop. You get a glass of water, drink it, and think...

"Now what?"

How do you get started on a story that you already love? You've put so much work into it already, so why doesn't it just happen? Why can't you get traction on the idea?

This morning over coffee, I pondered the idea of traction versus tread. When your boots or tires have worn out tread, you lose traction on the trail or road. Traction is what happens when you are already moving, awkward opening paragraphs behind you. So maybe the problem with starting a story isn't that the concept doesn't have traction -- how can it, if the story isn't in motion yet -- but that your story needs better tread.

I am really, really trying to avoid the sole/soul pun. It hurts me.

What is story tread, then?

First off, what I mean my "story" is more than just the plot. It includes your plot, but it is also your purpose, your theme, your characters, your created world -- in short, everything. It is the thing of beauty that you are bringing into the world. We sometimes say that a story is "plot driven" or "character driven." You may benefit from deciding which kind of story you plan on telling, before you get started.

I would say that a plot driven story is one where your characters ride in the plot bus, all carried along together for the purpose of where that bus is going. On the plot bus, narrative points of view can change while the plot keeps a steady forward motion. A character driven story would be one with all the characters making their way on their own power, sometimes staying in a group, sometimes not. In that kind of story, it may be best to keep the point of view to one character's observations.

Either way, you will want good tire tread and boot tread, because there are times in a first draft when the plot bus breaks down, and your characters will need to get out and walk to get to the end of the story. Vice-versa, you may have characters that want to make camp at a pleasant spot, suspecting you (rightly) of making their lives decidedly worse ahead, and the only way to get them moving is to put them on a trailer. If you have tread, every step you put down provides forward motion to the next one. Whether you are running through a fun page of dialog or tip-toeing through a delicate scene important to your theme, you want good footing.

Tread comes from depth and texture. Look at your characters' histories. What wants and needs motivate each of them? Why is your main character taking this story journey? For that matter, why are you, the author, taking this story journey?

Is it for the scenic views, as in a memoir or a slice-of-life comedy? A friends-to-lovers romance benefits most from a journey that takes its time, lingering on scenes of interaction and savoring character dynamics. A fantastic, playful story like Alice in Wonderland is about the journey, with the conclusion being of lesser importance than the wonder of Wonderland. Brave New World is more about theme than the world or characters as individuals, or even what happens to them. (To tell the truth, I've read that book three times and can't recall the conclusion of the plot at this moment.)

Scenery is the tread for those kinds of stories, so if you find yourself stalled, imagine any kind of scene you would like to happen in your story. Don't worry about chronology or where it fits in with your story plans. Even if you don't end up using the scene in your final draft, every scene you write deepens the grooves in your story and gives you more power to keep going. That unused scene might even develop into a free-standing short story.

Contrast a friends-to-lovers -- a staple of fanfiction -- story with a "fix-it," the kind of story created expressly to give a character a happier ending or "correct" an unsatisfying element. In a fix-it story, the ending or series of ending moments through the story is the story's reason for creation. A goal focused story, as the majority of stories are, is the kind most likely to get stuck in a mud puddle. For this kind of story, your characters are going to need a lot of agency, that personal power to get through the rough terrain. Even an empowered character can leave you slipping in the mud, unable to move forward in writing that character's story. You'll have to look deeper to create tread so that you can use that agency. What is it in your story that empowers that character? I don't mean, "what is it in the character that empowers the character." Specifically in your story, there will exist elements that your character uses.

For example, in Sherlock Holmes stories, Holmes observes everything, and Watson observes Holmes. Sherlock Holmes stories are, on the surface, about the solution of the mystery. How the detective gets to that solution is opaque to narrator Dr. John Watson. However, we love the stories because we get to watch Holmes work, through Watson's observations. It's no wonder that the most current interpretation of the stories, the BBC series in modern setting, has its focus as much (or more) on how John Watson and Sherlock Holmes affect each other than the reinterpretations of the mysteries.

Stephen King's The Stand is a story that moves from the decimation of the country's population toward a final "big boss" battle. The survivors of the superflu carry the story along a literal path and provide an answer to "What happens next?" through the gathering and separation of these survivors into groups. In a very different approach to monsters, Pixar's Monsters University, a prequel to Monsters, Inc., knows that the audience expects the prequel to show how Mike and Sulley end up as best friends working at the scare factory. They become rivals shortly after first meeting, so of course, the story has to show how their animosity grows into a friendship that will last, a well-established trope.

A trope is essentially the opposite of tread. A trope is shallow, smooth with familiarity, a surface made slick by omnipresence. A trope isn't necessarily bad. Used well, it provides resonance. But a trope by itself doesn't give you any purchase.

What I see moving the story forward from one scene to the next in Monsters University is the motivation of what the characters think they want (to outdo each other, win the contest, etc) while making the audience think they know how the story will end. The "twist" in the end, which completely makes sense, comes from looking at the story from the author's eye view. Remembering that the reader or viewer is a participant in your story can keep you going if you think about what kind of response or effect you want your reader to be feeling next. (Mwhahaha.)

One of my favorite Disney animated films has source material that gave the studio writers trouble because of a flat plot: Beauty & the Beast. In the original story, after the beauty is in the beast's castle, only a series of dinners happens until she returns home to her sick father. To make a dynamic animated film engaging to young audiences, Disney had to come up with more things happening. A musical montage alone wasn't enough on its own. A clear antagonist that was not also the love interest didn't suffice. Still, this movie is all about the end goal of Belle and the Beast becoming realizing their love for each other. The physical transformation of the Beast back to human is denouement. (You know you've grown up on animated animal anthromorphism when, like Belle, you look askance at the rose-lipped human prince and wonder what was wrong with the Beast staying as he was.)

The musical montage of "Something There," which takes the place of the static dinners/proposals and refusals of the original story, wouldn't have much impact without the plot point just before it. Belle runs away, gets attacked by wolves, but is saved by the Beast who has gone after her. Because he sustains injuries in saving her life, Belle starts to rethink her impression of him.

Beauty & the Beast succeeds with forward motion because it is a story that clashes egocentric characters into conflict with each other. They individual goals dig into each other, providing traction. The Beast was cursed because he had no empathy for a poor crone seeking shelter, and until he is gentled by interacting with Belle, he continues to show possessiveness and selfishness. Sending Belle home to her father shows that he has learned to think of her happiness over his own. The villain, vain and cruel Gaston, is the most obviously egocentric. He fits comfortably into the driver's seat of the plot bus when the time comes to "kill the beast!"

As a reader with my head in the clouds all the time, I identified with Belle, although at the time Belle seemed flawless. From an perspective of age, I can see that Belle, too, starts out with egocentricity in her nature. Although she does take her father's place as the Beast's prisoner, something that seems like a selfless act, it is as much fueled by her romanticism and desire for "so much more than her provincial life" as it is by her protectiveness of her father.

It's interesting to note how in the stage musical, which I saw just a few years ago, Belle's low regard for her "provincial" home and yearning for adventure become challenged by actually getting that adventure that takes her away from home. Once she becomes the Beast's captive, in the added song "Home" -- a significant character arc point -- she realizes the weight of her actions. Her positive influence on the Beast is getting him to see that there is a bigger world outside his castle. The more recent Disney interpretation puts more emphasis on both of the characters growing as people.

I'm finding it helpful to think in terms of tread. It's another way to talk about development, in concrete, visual terms. In the early drafts of a story, you still have time to add depth to your tread. You will need to do some of this in editing, too, but you can't edit a story that you haven't written.

Monday, June 9, 2014

Anticipation: the good tension

As the in-world time folds toward a significant event in a story I'm writing, I want the reader to anticipate the sharp moment of the event. Like a hand fan closing, the story needs to move toward that snap. In a larger sense, the story is moving toward a climax, but readers won't be able predict the climax so early on, if I'm doing my job right.

It's the end of Act I. Our Heroine will experience a change in her understanding that sets her up for Act II.

I find myself thinking about how fun it is to enjoy a story where you feel carried along on a clear path, but you are enjoying the ride enough not to look ahead and speculate -- at least, not overmuch. It can be disappointing to guess the ending. It's even more disappointing when the ending is a mismatch for the ending that seemed to be coming.

Anticipation is a good tool for managing audience expectation. It has the benefit of creating a fun kind of tension, like knowing of an upcoming vacation. A few years ago, a study by researchers in the Netherlands showed that the anticipation of a vacation increased people's happiness greater than the vacation itself. Readers have two kinds of anticipation. They can look forward to the opportunity to read the book (because who gets the time or has the stamina to read something straight through, beginning to end?), and they can carry hopes for what will happen in the story.

Pacing in a written work is different from the pacing of a movie or television show, where the pacing is part of the real time it takes to show the story visually. In written work, the reader participates in pacing by reading speed and time to read, which affects the pacing in the narrative structure. The writer can't control when the reader has to stop; the writer can only make it hard for the reader to put the story down.

If the story is a retelling, part of a series, a licensed world, or a fanfiction, then the raw elements "package" includes items that the reader wants and expects. A good story of this type uses familiarity to carry the reader along. For example, Sherlock Holmes fans wonder how the latest incarnation of Holmes will address the role of Doctor John Watson; the nemesis, Professor Moriarty; the one woman who outsmarted Holmes, Irene Adler; and the "death" of Holmes at Reichenbach Falls. Whether or not Holmes's use of "the seven percent solution," his disguises, or the Baker Street Irregulars are included seem to be lesser elements that may or may not be utilized. Sure, the story has to have original elements to keep it from being a boring rehash of the original work, but if the new story doesn't have familiar characters, story points, and/or world elements addressed in some way, the reader is going to feel anxious when they don't appear and will feel cheated by the end.

An original work gets to create that waiting-for-the-last-day-of-senior-year feeling more freely, but all stories still have a toolbox from which to draw. The template of the genre provides some. The story may draw on tropes with a wink at the savvy reader. In my opinion, a good story uses multiple elements to create that good tension, and the most important one is that it develops the secondary characters as fully as the main character, through the series of interactions that happen throughout the story. Good characters carry a story. This sounds like writing 101, and it is, and here's why: looking forward to a vacation get-away is happiness-increasing anticipation, but looking forward to a vacation with someone you love to be with is twice as good. If your readers want to spend time with your characters, they will look forward to the next opportunity, whether that's the next chapter or the next book.

Sunday, May 11, 2014

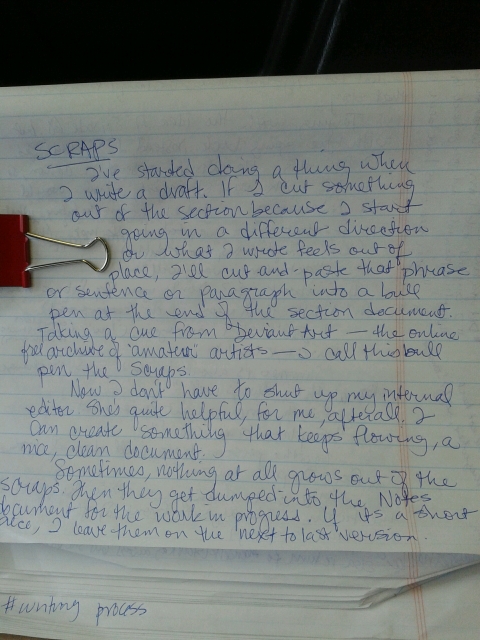

Scraps

I've started doing a thing when I write a draft. If I cut something out of the section because I start going in a different direction or what I wrote feels out of place, I'll cut-and-paste that phrase or sentence or paragraph into a bull pen at the end of the section document. Taking a cue from Deviant Art -- the online free archive of "amateur" artists -- I call this bull pen the Scraps.

Now I don't have to shut up my internal editor. She's quite helpful, for me, after all. I can create something that keeps flowing, a nice, clean document.

Sometimes, nothing at all grows out of the Scraps. Then they get dumped into the Notes document for the work in progress. If it's a short piece, I leave them on the next-to-last-version.

Saturday, April 5, 2014

Sketching on Napkins

Written on the back of an envelope from a received payment. The postmark, printed on the back side, almost looks like a stamped chop.

If I were to sum up my father’s character in one image, it would be of him at the table of a restaurant, discussing an idea, in conversation, sketching on a paper napkin to illustrate a design. He would be using his Monte Blanc fountain pen. Incidentally, this is the same image that I would use to describe creativity.

Creativity isn’t the bold use of colors and shapes. It’s not using all the crayons in the box to color a picture. Creative force flows like fountain pen ink onto a white paper napkin. It doesn’t wait for conditions to be perfect: perfect materials, perfect venue, or even perfect audience. (As often as not, we kids were my dad’s audience over brunch.) It’s inspiration landing on any surface. It’s the active mind moving the active hand. It’s about creativity being part of who you are, not a hobby.